Trump dissing Fed chief Powell is new only to the extent that the former is rude. Plenty of govt bosses, in the West or in India, have had a go at chiefs of central banks. Govts like cheap money, it’s feel-good. Central banks hate inflation . There lies the tension

Jerome Powell may still be a marked man. Trump now says he won’t sack him. But you never know with Trump. He called Powell “Too Late” for dithering in the face of the 2022 inflation surge. Also, “low IQ”, “very stupid”, “average mentally person”, and declared, “I think he’s doing a terrible job.” Yet, Trump is at a loss: “I do it every way in the book. I’m nasty. I’m nice. Nothing works.”

Now, Trump’s aides are trying a pincer over the alleged $700mn cost overrun in the Fed building’s renovation that might let them pin Powell to the mat in his last year as Fed chair. Or not. Powell, after all, has been here before.

‘CRAZY’, ‘LOCO’

When Trump picked Powell over Janet Yellen late in 2017, he was, in the President’s words: “strong, committed, smart”, someone who would provide the Fed “the leadership it needs in the years to come”. But six months into his first term, he was already out of favour.

A non-economist — Powell’s a lawyer by training — he was expected to toe Trump’s line on interest rates . Basically, keep interest rates low to spur growth, boost stock prices, and ensure Trump’s re-election in 2020. Powell turned out to have a spine, and by Aug 2018 Trump was calling the Fed “crazy”, “loco”, “gone wild”. He told The Wall Street Journal: “(Powell) was supposed to be a low-interestrate guy. It’s turned out that he’s not.”

INTERESTED PARTIES

The crux of the Trump-Powell feud is the cost of money, or interest rates. Govts universally want money to be cheap, so that businesses don’t hesitate to borrow for expansion. Expanding businesses add jobs, GDP grows, stock markets zoom, and everybody lives happily ever after.

However, cheap money can also drive up prices, or inflation, and when things cost more, people buy less, so businesses put off expansion. And if demand falls too much, jobs are lost, and everybody is miserable.

So, central banks universally aim to keep price rise in check with interest rates. But because interest rates, unlike Schrodinger’s cat, can’t be in two states — high and low, in this case — at the same time, govts and central bankers with a spine must agree to disagree.

NIXON WAS WORSE

History repeats itself. In 1969, Nixon picked Arthur Burns to head the Fed. Like Trump, he believed Burns would prove pliant, and just to be sure he told him: “I know there’s the myth of the autonomous Fed…” To ensure everyone else also got this, he declared at Burns’s swearing-in: “I respect his independence. However, I hope that, independently, he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed.”

Nixon wanted low rates with an eye on the 1972 election, and we know from the “Nixon tapes” that he told Burns in Oct 1971: “Liquidity problem (too much money in the system)... is just bullshit”. Burns obliged. His rate cut stimulated the economy in the short term and handed Nixon a landslide victory, but then caused an inflation problem that lasted a decade, and became the strongest argument for central bank independence (CBI).

INDEPENDENCE DAYS

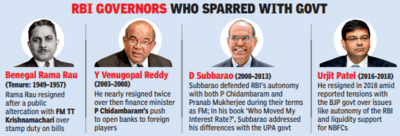

Central banks like RBI and the US Fed are a relatively recent development. Before WW-2, they were merely the lenders of last resort. After the war, setting interest rates became their job, but with plenty of govt interference. In India, RBI governor Benegal Rama Rau quit in 1957 after a face-off with finance minister T T Krishnamachari. During the Vietnam war, President Johnson summoned the Fed chair to his ranch and criticised the prevailing monetary policy .

Even Milton Friedman, who coined the term ‘central bank independence’ in 1962, wasn’t in favour of all-powerful central banks. He wanted govt to set central bank objectives, and banks to attain them using policy instruments like interest rates — without further interference. CBI was important for central banks to function without fear of criticism from a man like Trump, especially since there’s a lag between policy implementation and results.

Over a century from 1923, CBI has risen around the world. Trinity College professor Davide Romelli’s analysis shows 370 banking reforms across 155 countries — 279 of these increased CBI and 91 reduced it. Globally, the CBI index rose from 0.35 in the 1970s to 0.6 by 2020.

That’s why Trump, when he brought “independent” govt agencies under his thumb with an executive order, made it clear that “This order shall not apply to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or to the Federal Open Market Committee in its conduct of monetary policy.”

TUSSLE CONTINUES

Still, the old tussle for control over monetary policy continues. The Chidambaram-Subbarao standoff over interest rates in 2012, RBI governor Urjit Patel’s resignation in 2018, resignations of two Argentine central bank chiefs — Martin Redrado in 2010 and Juan Carlos Fabrega in 2014 (Luis Caputo’s 2018 resignation was under IMF pressure) — and Japanese PM Shinzo Abe’s choice of a “like-minded” central bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, in 2013, are all examples of govt’s upper hand.

But govt assertiveness over central banks takes a toll on stocks and bonds. For example, the S&P 500 dipped 2.4% when Trump called Powell a “major loser” in April. That’s why he can’t use a hammer to dislodge the Fed chief. What he can do is try to pry Powell off with a screwdriver, and that’s what he’s doing.

Jerome Powell may still be a marked man. Trump now says he won’t sack him. But you never know with Trump. He called Powell “Too Late” for dithering in the face of the 2022 inflation surge. Also, “low IQ”, “very stupid”, “average mentally person”, and declared, “I think he’s doing a terrible job.” Yet, Trump is at a loss: “I do it every way in the book. I’m nasty. I’m nice. Nothing works.”

Now, Trump’s aides are trying a pincer over the alleged $700mn cost overrun in the Fed building’s renovation that might let them pin Powell to the mat in his last year as Fed chair. Or not. Powell, after all, has been here before.

‘CRAZY’, ‘LOCO’

When Trump picked Powell over Janet Yellen late in 2017, he was, in the President’s words: “strong, committed, smart”, someone who would provide the Fed “the leadership it needs in the years to come”. But six months into his first term, he was already out of favour.

A non-economist — Powell’s a lawyer by training — he was expected to toe Trump’s line on interest rates . Basically, keep interest rates low to spur growth, boost stock prices, and ensure Trump’s re-election in 2020. Powell turned out to have a spine, and by Aug 2018 Trump was calling the Fed “crazy”, “loco”, “gone wild”. He told The Wall Street Journal: “(Powell) was supposed to be a low-interestrate guy. It’s turned out that he’s not.”

INTERESTED PARTIES

The crux of the Trump-Powell feud is the cost of money, or interest rates. Govts universally want money to be cheap, so that businesses don’t hesitate to borrow for expansion. Expanding businesses add jobs, GDP grows, stock markets zoom, and everybody lives happily ever after.

However, cheap money can also drive up prices, or inflation, and when things cost more, people buy less, so businesses put off expansion. And if demand falls too much, jobs are lost, and everybody is miserable.

So, central banks universally aim to keep price rise in check with interest rates. But because interest rates, unlike Schrodinger’s cat, can’t be in two states — high and low, in this case — at the same time, govts and central bankers with a spine must agree to disagree.

NIXON WAS WORSE

History repeats itself. In 1969, Nixon picked Arthur Burns to head the Fed. Like Trump, he believed Burns would prove pliant, and just to be sure he told him: “I know there’s the myth of the autonomous Fed…” To ensure everyone else also got this, he declared at Burns’s swearing-in: “I respect his independence. However, I hope that, independently, he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed.”

Nixon wanted low rates with an eye on the 1972 election, and we know from the “Nixon tapes” that he told Burns in Oct 1971: “Liquidity problem (too much money in the system)... is just bullshit”. Burns obliged. His rate cut stimulated the economy in the short term and handed Nixon a landslide victory, but then caused an inflation problem that lasted a decade, and became the strongest argument for central bank independence (CBI).

INDEPENDENCE DAYS

Central banks like RBI and the US Fed are a relatively recent development. Before WW-2, they were merely the lenders of last resort. After the war, setting interest rates became their job, but with plenty of govt interference. In India, RBI governor Benegal Rama Rau quit in 1957 after a face-off with finance minister T T Krishnamachari. During the Vietnam war, President Johnson summoned the Fed chair to his ranch and criticised the prevailing monetary policy .

Even Milton Friedman, who coined the term ‘central bank independence’ in 1962, wasn’t in favour of all-powerful central banks. He wanted govt to set central bank objectives, and banks to attain them using policy instruments like interest rates — without further interference. CBI was important for central banks to function without fear of criticism from a man like Trump, especially since there’s a lag between policy implementation and results.

Over a century from 1923, CBI has risen around the world. Trinity College professor Davide Romelli’s analysis shows 370 banking reforms across 155 countries — 279 of these increased CBI and 91 reduced it. Globally, the CBI index rose from 0.35 in the 1970s to 0.6 by 2020.

That’s why Trump, when he brought “independent” govt agencies under his thumb with an executive order, made it clear that “This order shall not apply to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or to the Federal Open Market Committee in its conduct of monetary policy.”

TUSSLE CONTINUES

Still, the old tussle for control over monetary policy continues. The Chidambaram-Subbarao standoff over interest rates in 2012, RBI governor Urjit Patel’s resignation in 2018, resignations of two Argentine central bank chiefs — Martin Redrado in 2010 and Juan Carlos Fabrega in 2014 (Luis Caputo’s 2018 resignation was under IMF pressure) — and Japanese PM Shinzo Abe’s choice of a “like-minded” central bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, in 2013, are all examples of govt’s upper hand.

But govt assertiveness over central banks takes a toll on stocks and bonds. For example, the S&P 500 dipped 2.4% when Trump called Powell a “major loser” in April. That’s why he can’t use a hammer to dislodge the Fed chief. What he can do is try to pry Powell off with a screwdriver, and that’s what he’s doing.

You may also like

Epstein scandal: Trump orders release of 'any and all' case files; Pam Bondi vows 'ready to move the court'

US Declares The Resistance Front A Foreign Terrorist Organisation

McVities changes name of popular biscuit after removing vital ingredient

Today's horoscope for July 18 as Scorpio resists the urge to quit

Man Utd star has gifted Bryan Mbeumo perfect welcome present ahead of £70m transfer